THE “ALMOST” PERFECT CRIME

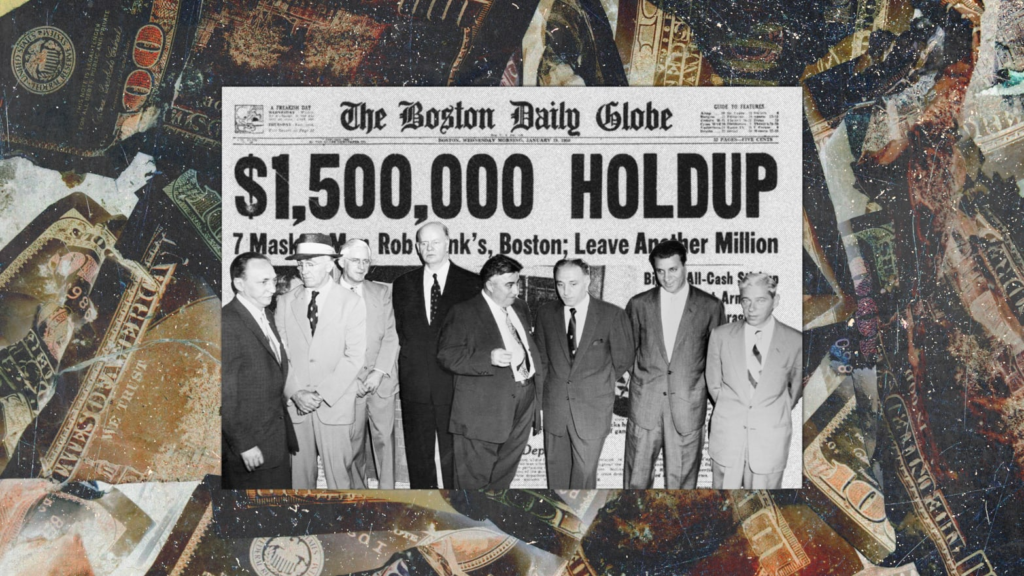

Along with my passion for history, I have always loved mysteries and perfect crimes that go wrong. The infamous Great Brinks Robbery in Boston, Massachusetts, that happened on this date (January 17) in 1950 and was described at that time as the “Crime of the Century,” contains elements of all three.

This is the way it supposedly happened:

Just as the employees of the security firm Brinks Inc, in Boston, were closing for the day on the evening of January 17, 1950, they began to move sacks of undelivered cash, checks, and other items to the safe on the second floor of the building.

Suddenly they were confronted by between five to seven (numbers varied), heavily disguised men wearing gloves who threatened and bound the employees as they quietly stole and made off with more than $1.2 million in cash and another $1.5 million in checks and securities, making it the largest robbery in the United States at that time.

A Brink’s employee was eventually able to get loose and telephone the Boston Police Department. Minutes later the police arrived, joined quickly by FBI special agents, but there were few clues left behind to follow up on. The robbers had been careful by wearing gloves, Halloween-type masks, and after interviewing the employees, it was also learned the robbers had worn soft shoes to muffle their footsteps and did little talking while carrying out their operation. They had planned the heist with great precision.

There were a few other clues to follow up as further details came to light and because of the FBI involvement, the criminal underworld was thought to be involved in the crime. Nonetheless, every lead always came to a dead end. Brinks even offered a $100,000 reward but to no avail. It appeared that the perfect crime had indeed been committed. Many rumours circulated, one of which even involved the infamous Purple Gang of the 1930s that were thought to have resurrected their activities and been involved in the heist.

And then, on the night of January 17th, 1952, exactly two years to the day after the crime occurred, an anonymous caller contacted the FBI’s Boston office, saying he was sending a letter identifying the robbers. This call linked eleven well-known gangsters with the crime. Their names were as follows:

Joseph McGinnis, Joseph O’Keefe, Anthony Pino, Adolph Maffie, Thomas Richardson, Vincent Costa, Michael Geagan, Henry Baker, James Faherty, Joseph Banfield and Stanley Gusciora.

A full-scale investigation followed over the coming years, taking the FBI in many different directions with fascinating stories about all the gangsters and their nefarious activities. Eventually, just five days before the statute of limitations on the crime was to run out, the FBI made some arrests, and a trial later took place.

Of the eleven people involved in the robbery, eight received life sentences, with two dying before they could be convicted. One, Vincent Costa, was released from prison in 1969 after being paroled but was arrested again in 1985 and charged with cocaine trafficking. Michael Geagan was also released in 1969 after being paroled. The last surviving member of the group was Adolph Maffie, who died in 1988 at the age of 77.

The most intriguing part of this story is that less than $60,000 of the more than $2.7 million stolen was ever recovered. So, what had happened to the remainder of the money?

This perfectly executed crime had received a great deal of press coverage and was eventually even adapted into four movies: Six Bridges to Cross (1955); Blueprint for Robbery (1961); Brinks: The Great Robbery (1976) and The Brink’s Job (1978).

So, in the end, the “perfect crime” had a perfect ending—for everyone but the robbers!